Sometimes the greatest adventures unfold from an ambitious goal confounded by errors and bad judgement, redeemed by luck, faith, tenacity or even something like grace.

My heart suffered from some lost love; the kind of ache that troubles even a peaceful soul. To take the edge off that pain, I sought to put myself on an adventure that demanded my full concentration, enforced by the potential of death, an edge to take the edge off.

For me, that meant a free-solo rock-climb, climbing a technical route with no ropes, by myself.

The question was “Which adventure could be the medicine? I had already free-soloed most of the routes that I dared solo on-sight (having never climbed before) Something I had previously soloed would be too predictable to have the desired effect. Free-soling was my Zen samurai meditation. It was also a lazy joy, no need of finding a partner, fiddling with rope and gear, just moving over stone in beauty, harmony and focus.

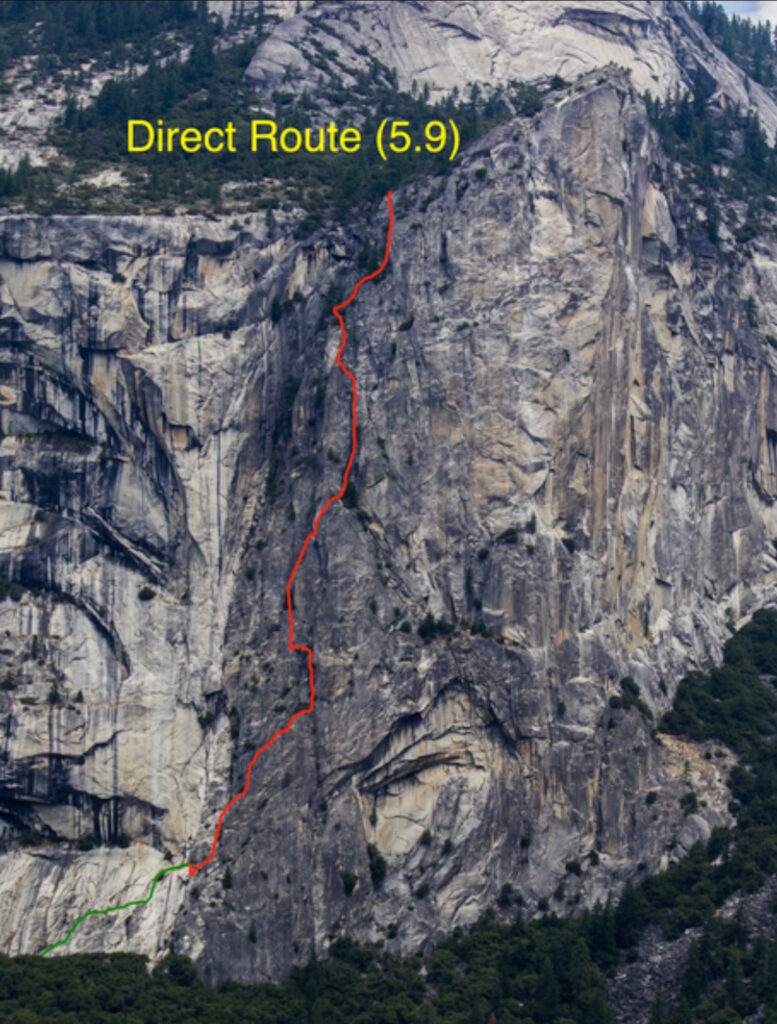

There is a 1200 foot “Direct” route up the pillar of “Washington Column” in Yosemite Valley. It was rated 5.7 on the difficulty scale. I’d never heard of anyone who ever climbed the route, and I knew a lot of Yosemite climbers. Still, it used to be a popular route back when rock-climbing was evolving from mountaineering. It was first climbed in 1940. I didn’t give due consideration to the fact that in those days, 5.9 was the hardest grade on the scale: many “Old Skool” 5.7s were now considered far harder in modern terms.

Still, how hard could it be? Seemed like the good idea for a day of adventure, and I set off.

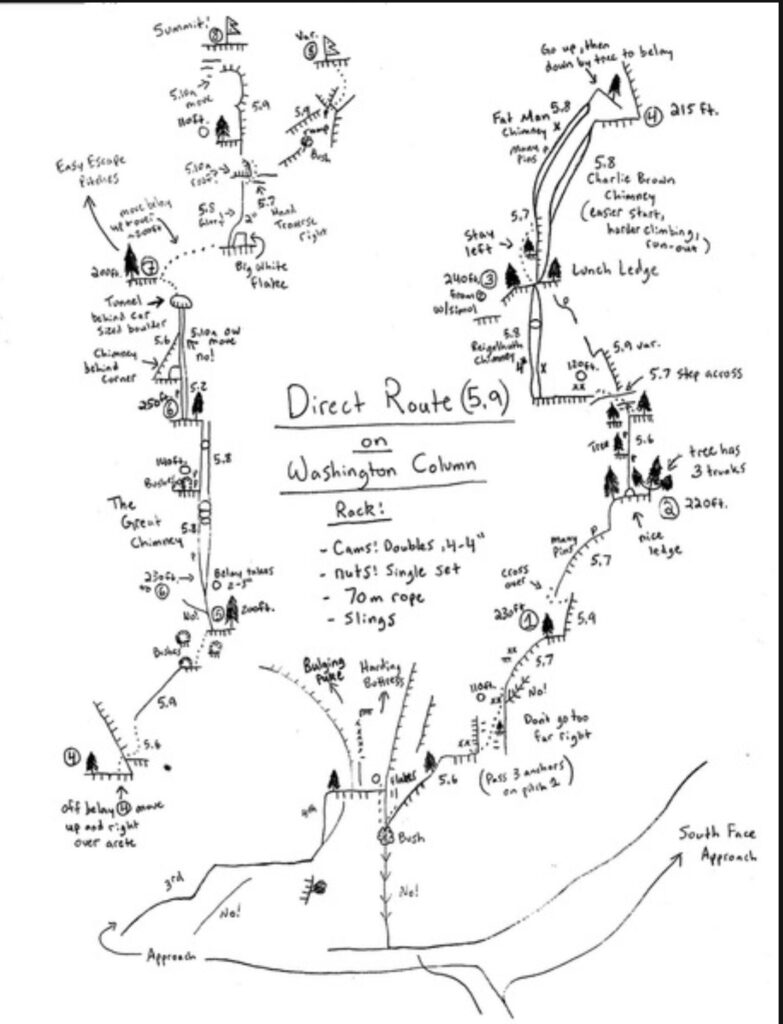

The other problem was going to be route-finding. Modern rock-climbs are outlined with graphic maps, detailing where to go and where difficulties and landmarks are present. This route only had frustratingly cursory descriptions in a defunct guidebook with guidance like

“…climb an inconspicuous crack system 25 feet to the left. This system soon turns into a decomposed, tricky 5.7 slot-the notorious Fat Man Chimney. About 140 feet above Lunch Ledge, traverse down and right to a good belay ledge by a tree. Next, move up and right over a difficult friction step to a sandy slope below the forbidding Great Chimney….”

Still, how hard could it be?

I hiked to the base of the cliff, and found my way up into what I hoped was the route. I climbed higher and higher but instead of the worn lichen betraying the route on well traveled route, there were many options and old pitons left in the rock sometimes gave hints.

The climbing wasn’t desperately hard, but there was often several possible ways to go; choosing the wrong way could lead into no-man’s land, checkmate for free solo, so I strained to discern the true path.

This was not easy since the route was rarely done anymore. The description didn’t help much.

About 700 feet above the ground, I was climbing a crack that seemed like the “obvious” choice. As I ascended, the climbing got harder and harder, and the rock become decomposed and sketchy to trust. I reached a point that was hard and insecure enough that I told myself. “this is the point of no return, I will not downclimb what I am now ascending.”

That crack ended at a ledge where I could stop and take stock of my situation. Looking up, my eyes followed each upward feature and, distressingly, they all looked like dead ends. There was no way to continue up! I looked again and again, hoping I had missed something,

Looking around further, I discovered off to my right was the obvious “Forbidding Great Chimney” a defining feature of the climb. It was completely out of reach. That is, unless I downclimbed the crack that I swore to myself I would not dare downclimb!

Oh if I could only get to the sweet “Forbidding Great Chimney”!

At this point, nearly checkmated. I took stock of my options.

The wise and humble option would be to yell and scream for a rescue. It might take hours to catch anyone’s attention, if ever I was a long long way up, and far longer for a rescue to reach me. Probably I’d have sit on that ledge all night into the next day. Still, I would live.

I was young and male, this humiliating idea repulsed me.

The other option would have been sucking it up to downclimb the feared hard section to get back on-route. Realistically, this would have been far safer and smarter than what I actually did.

There can be times when wisdom fails and foolish prevails.

This was my time for that. I tempted fate in a manner that would never make sense to anyone, including me.

I noticed that about 35-40 feet directly below me, there was a ledge about 6 feet wide, and it led over the promised chimney of likely redemption. It was way, way too far to jump. The wall below was nearly vertical and blank with just a few unconnected features, but I hatched an exploratory plan.

I had some climbing webbing and slings wrapped around my waist, and few little pieces of gear just in case I hit a tight spot. I tied the webbing and slings together into about a 10 foot line. I had a piece of gear, an “RP” nut, smaller than a fingernail but thicker, with a wire loop, I tied the slings to the loop and wedged it into a thin crack.

(This is insane but somehow I felt to do this…)

I lowered myself hand over hand down the rock using those slings until I was near the end. I was still far far too high to jump. I could have aped back up the slings and maybe saved myself but instead….

I noticed there was a tiny crack where I was and a tiny stance for my feet. If I could only retrieve the gear and slings I just used to descend, I could do it all again and maybe get closer to the ledge and freedom.

But I had just wedged that gear in tightly by hanging on it with my body weight. It shouldn’t come out from below.

But I stood on that stance and whipped the slings up and down, back and forth, trying to dislodge the piece of gear I had been hanging on.

Once I started, there was no way I could trust that gear to re-ascend the slings so now it became a do or die mission.

I determined spend hours if need be, however long it took, whipping that gear back and forth, praying to God, doggedly, trying to get that gear, and my slings back.

I trusted in grace, because only grace could save me at this point.

After some timeless time, and not a short time, miraculously, the whipping dislodged the gear which came flying back to me. I gave thanks and placed the same tiny nut in the crack at my waist, gave it a yank, and repeated the process of lowering myself down the face toward the ledge.

When I reached the end of the line, literally, I was hanging by one hand staring at the remaining distance to the ledge I was aiming for. I was further than I had hoped to reach and there was nothing but a blank face of rock there.

I seemed inconceivably far to consider jumping but, now that I was hanging by one hand on a blank face, it was inevitable that was the only choice left and I might as well face it rather than waste my remaining strength and be forced to let go anyway. The ledge was maybe 10 feet below my feet but that’s 15 feet below my eyes. Sounds like a little, but look at an eight foot ceiling and imagine yourself 700 feet above the ground.

Once again invoking the divine, I focused on the act, absorbing the fall on the ledge, trying to both avoid injury and tumbling past the ledge to the 700 foot fall beyond it.

Sometimes Rock-climbing seemed like a non-violent outlet for the warrior spirit. Now was the time of battle to run into oncoming fire. In an instant, I was going to be tumbling to my death, crumbled on a ledge with broken ankles, so somehow saved despite the odds.

Ready, Set, I let go, knowing this was a defining moment in my life. A moment timeless in the air, I landed with both feet on the ledge, absorbing the shock as best I could, and Shazam!, I took stock of my situation. I hadn’t broken my ankles. I was OK!! It worked!!

Thanking God, the spirit animating my lift, and perhaps some patron saint of fools, I traversed to the “Forbidding Great Chimney” which was reputed to be the hardest point on the route, but it was actually a joy in light of what I had been through.

The deep chimney, a body sized slot of a vertical chasm of a crack, ended in a wide ledge below a steep final headwall leading to the rim of Yosemite Valley.

I thought I should be home free at this point but I couldn’t believe my eyes. There were about three possible routes to the summit and they all looked far far harder than what I would have considered free soloing on-sight,

(one modern map calls one 5.9 and the other 5.10)

No going back at this point, I just had to decide the more promising line and struggle up it to the top.

I remember the joy of victory and redemption at the top.

I remember nothing of the long and still a bit dangerous decent back to the valley floor or anything else about the rest of the ensuing night. Once I was saved, my enhanced reality from the self-battlefield congealed back into extraordinary ordinary life on the rim of the outstanding beauty of my beloved Yosemite Valley.

This Valley was my real committed relationship and despite my foolishness, she fulfilled my trust in her miraculously. If you love a place, it loves you back. If you know there are no accidents and that we live in a kind of a dream, even if you have lost your judgement, sometimes reality becomes fluid enough to make the impossible manifest.

I swore I would never go back to that climb

But

Years later the nightmare dimmed, I forgot the gnarly parts, the adventure beckoned. I was tempted to revisit this adventure, again solo, and I somehow there I was climbing this route again. I hadn’t remembered much of anything about it except the great chimney and the hard choices to get to the rim.

This time I actually found the “Notorious Fat Man Chimney” as the previous time I had inadventently climbed a various the “Charlie Brown Chimney” a harder and cleaner variation.

I remember bridging across the rotten and insecure Fat Man Chimney. I felt a wave of gratitude for my life, the people who loved and supported me, my folks back home, I felt a wave of tears, paid respect and finished the passage.

Higher up, I looked to see if my old slings were still hanging on the face above the ledge. They could only have been removed by wind and weather of if someone had got lost like me and rappelled past them and took them. They were gone.

Finally in the end I was reminded of how hard those final cracks to the summit looked and I had zero memory of which one I climbed the last time. And I don’t remember which one I climbed that time either.

They say those who don’t remember the past are doomed to repeat it. I don’t know about that but it’s happened more than once to me climbing, Repeating some tortuous epic that beat everything trivial out of me for a time.

It’s a valuable crucible that comes with a price, one I have been fortunate enough to afford.