I had loved living and working in Yosemite Valley for three years, but it was time to return to my university education. It had been a magic time, living in beauty and learning to rock-climb. I wanted a gesture to the place, to myself, and to life to celebrate all this, a grand adventure.

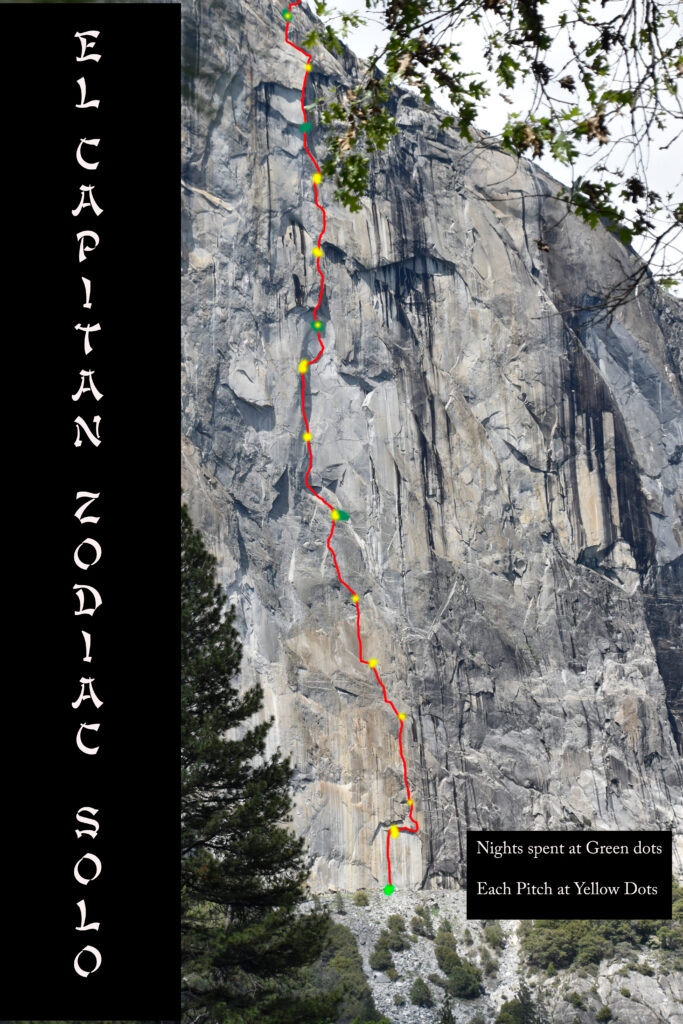

I chose to attempt a solo ascent of a 2000 foot overhanging route on El Capitan, the Zodiac route

It would be the most epic challenge I could imagine without being reckless or stupid (according to me anyway.) I had only done three multi-day rock-climbs before this, including one shorter solo. This climb would take about a week and be a significant step up.

The “Zodiac” route had only been soloed two or three times by 1982; rated A3+, still challenging climbing given the more primitive gear available at the time, it would require a hammer and pitons

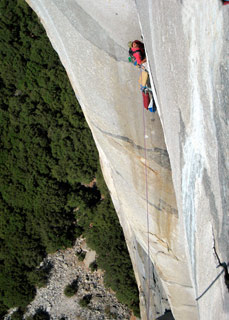

I was infatuated with beautiful 450 foot circle of pure white granite in the heart of the route.

The crucible in stone would make a final romantic poem from me to Yosemite.

I meant “final” to mean “until I return” but I was aware many poems are tragic.

I was studying the map of the route when a black spider crawled across the page and stopped right on one of the crux pitches high on the route; the Mark of Zorro.

It gave me a dark feeling.

I knew I was creating a rite of passage for myself that had to have teeth to have meaning.

I carefully prepared the gear and supplies. A solo of El Capitan is a bit like a journey into space, or a sail across the ocean. A missing piece of needed gear could stop me cold. Too little food or water could lead to hours or days of suffering.

I couldn’t afford to drop anything important. Anything dropped would fall straight to the ground without touching the rock, so I attached webbing loops to water bottles, fork and spoon etc, so everything could be clipped in safely. Water alone weighed in at about 80 lbs. Thirst is torture when working hard climbing.

It was June, 1982, when my great friend and partner from work, Steve Brosig helped me carry the pig to the base of the route. I climbed a few hundred feet and hung ropes to the ground to spend my last untethered night at the base with my best high school friend.

Little did I know then that Brosig and I would attempt El Capitan ourselves years later, along with my Ex-girlfriend at the time. He would marry a different future ex-girlfriend of mine as time unfolded. Steve departed the world early from blood cancer, probably from toxins inhaled as a fireman. Nothing ever came between us. Looking back, I’m glad we shared moments like this.

I ascended the ropes in the morning, hauled the gear and began the routine of concentration and action that would consume me for days.

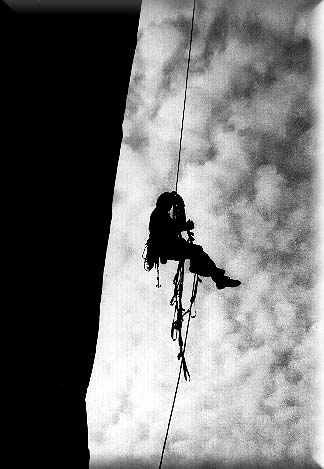

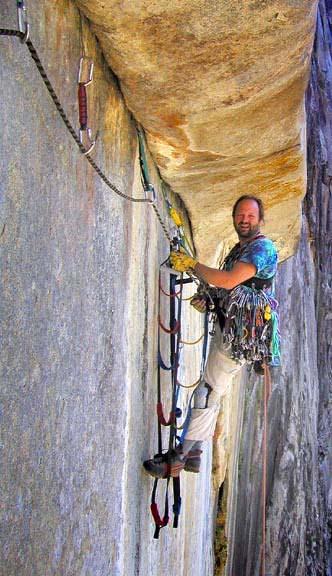

The solo routine is basically climbing the route twice, with no partner to share duties. I would climb each pitch (section of climbing, usually 100-160 feet) climbing with the aid of gear I placed in the rock, then rappel down a second rope. The rappels were stunning, hanging in space above a yawning void, followed by pulling myself back to the rock and the anchor where I started. I would lower the haul bag out to hang in space, and climb back to the top of the pitch, using rope ascenders, removing the gear I had left for protection in climbing.

Once at the top of the pitch, I would rig a pully system and strenuously haul the pig (climbers call haul bags “Pigs”) up to the new starting point and re-rig the system to repeat the process. Each Pitch would take 3.5 to 4 hours in total. I would spend each night on a small ledge or in a hanging cot called a portaledge.

Everything required mindful concentration because a mistake could cause tangles, hang-ups or mishaps that could cost anything from precious time to life itself.

Much of each day was spent assessing the stone right before my eyes, choosing the right gear, trusting my weight to it, climbing up to place the next gear. I was so immersed in the focus of my acts that it was impossible to dwell on any petty aspect of my life on the ground. I did have to live with a nagging state of background anxiety over my position, alone suspended over a yawning void. The repressed fear would build when I was on a questionable piece of gear; I would will myself to act in the face of exposure and dread, which would subside like a wave once a secure piece calmed my nerves.

At night, I was free from the need to focus. I could relax, eat and enjoy the view, but all the repressed stress from the day would rise to the surface when I tried to sleep.

Often I felt a sensation of sudden weightlessness and falling that shocked me to alertness just the brink of sleep.

It was a feeling I had anticipated many times earlier in the day. Falls while Aid-climbing (involving hanging on the gear) come by surprise, which breeds an insidious tension. A fall could come at any moment if the gear was marginal.

An aid fall begins with a sudden sharp sound, then a feeling of weightlessness, stomach rising in the chest, and a timeless awareness amidst the chaos. Often, the gear that fails hits you in the face just as you launch into the uncertainty. The sudden shifting of gear involved in the climbing process creates many false alarms daily. I never fell on this climb but was still haunted from previous falling experiences.

I delved so deep into the routine that after 3 or 4 days, it seemed like the only thing I had done in my life was climb that stone. I lost contact with the world of people, plants and animals. There was only the stone and the void.

My one respite from solitude was a nightly call on a CB walkie-talkie. My friend Steve would drive to El Capitan meadow and check on me. Sometimes he would bring a friend, or a beautiful woman friend he was trying to impress. That world of comfort and togetherness that beckoned me, only a stone’s throw away, yet unreachably distant.

I surrendered to the focus and solitude. Every day demanded full attention. Every morning began with chants and meditation. I invoked the Spirit at the beginning of each pitch and sometimes at crux sections.

I was a natural creature of the granite world days later by the time I reached peanut ledge, 300 feet from the summit. I had little doubt I could reach to top the next day.

That was until suddenly the weather changed. Even though it was near the end of June, it was getting cloudy, windy, cold and foreboding.

When rain came, I was at first protected by the overhanging rock above, but in no time, the water was blowing right back to me. Rain in June is ordinarily mild and brief. I hadn’t even brought a sleeping bag, just a wool blanket and some fleece clothing. I crouched on Peanut Ledge under my rainfly shivering and chanting. Sometimes the rain turned to snow. I thought of other climbers I knew of who died of hypothermia on El Capitan during sudden storms.

After an eternally long and cold night, I awoke to cloudy oblivion.

The fog that enveloped me occasionally parted to reveal the ranger vehicles parked in El Cap Meadow. They called to climbers on megaphones “Climbers on El Cap Tower, do you need a rescue? Raise one hand for yes, two hands for no…”

There were helicopters flying incessantly. I learned later that climbers had been plucked off El Capitan and Half Dome. My friend Mike Corbett was on a new route at the time that he first named “Riders on the Storm” but later changed it to “Pacemaker”.

I was shivering and miserable and sorely tempted to call for that rescue since rescues were going on all around me anyway. It was hard to know if and when the cold might take me or not but I was hanging on to this “do or die” intent. I had come this far. I would struggle to the top somehow.

I didn’t know if I was being stupid or strong, I just knew what my decision was.

Brosig was down in the meadow with Steve Shipoopi Schneider who delivered the weather report. He announced the storm was here to stay and I should consider climbing my way out of there if it was at all possible.

It was good advice.

During a break in the storm, I climbed a pitch off Peanut ledge. During another break, I climbed to within a hundred feet of the top. I set up my portaledge and hoped for the best. I could barely make a fist with my hands. I took two aspirin before going to sleep. I awoke later in the night and my whole body felt numb! All the nerves were deadened! This was a bizarre sensation, and concerning, but there was nothing I could do. I just had to accept reality and hope it was temporary.

The next day, I could feel my body again. I reached the top during a break in the storm. I felt a sense of deliverance to reach flat ground. The moment was tainted by the loathsome need to rappel back down into oblivion to clean the gear from the final pitch.

Soon my whole world was the top of El Capitan. Rays of sunlight streamed down between the clouds on my grateful countenance. I felt a soaring natural high.

I tried to dry things out a bit. Soon my friends Brosig and Kevin arrived to help me carry the gear down. In my state of mind, they were magical, mythical beings, glowing with life and energy. Even the plants seemed to pulse with a vitality in contrast to my week facing bare granite.

Walking was also a unique and joyful experience. I could step freely without fear or the burden of a heavy rack of gear. I felt like an astronaut bouncing on the moon in low gravity.

My friends offered me a small sip of wine which went right to my head. With great gusto and love, we three brothers headed for the descent route called “the East Ledges.” It rained and poured on us while rappelling during the technical sections of the descent, The ropes even got stuck for awhile. It didn’t matter. I knew we would overcome everything.

It was the perfect crucible, my passage via adventure into my new life. I would soon move to Berkeley to study Indian languages, religion and philosophy. Climbing was off the table. I bought a motorcycle to park on campus but also to have something to feel an edge with.

Zodiac became something of a route of destiny for me. I guided it 20 years later without using a hammer. Later, I guided it again after unknowingly rupturing my Achilles tendon falling on the first pitch.

Finally, I broke my arm in eight places when I accidentally dislodged a ton sized slab of rock that cut through the gear I was on and sliced through half the rope.

At that point I felt the universe was progressively suggesting I devote my time to other things and life unfolded beautifully but differently from then onwards.

I include some pictures from those other climbs as I didn’t bring a camera on the solo

What a fascinating journey! Thank you for sharing!